Tags

aquaculture, domestication, Garrett Hardin, Jacques Cauvin, oyster cultivation, Pascale Legué, territorialisation, tragedy of the commons, wild oysters

As a psychologist, I can think of no better point of departure than that of the Lacanian use of ‘territorialisation’, a term which describes how the infant starts to differentiate and organise its chaotic body, its organs and orifices, exuding the inner flow of corporeal liquids, into a libidinal structure of erogenous zones and part-objects on the dry-land of its skin to underscore terrestrial man’s relation to the sea. The infant’s primal struggle from its watery cavern at birth onwards to escape its feeling of drowning or choking in its own fluids mirrors the epic struggle of the first creatures to reach the shorelines of the coast. I would suggest that the parallel is no coincidence, although historically, territorialisation in its more traditional sense is closer to the phenomenon of colonialisation and designates a will to conquer and control what can seen as a threat, unknowable, perhaps even coveted, using the battery of techniques and methods man has employed on terra firma, ever since the dawn of domestication. Indeed, the two concepts of territorialisation and domestication seem to have much in common. One anodyne definition of the latter has been any form of human husbandry of other animals, mainly mammals, although the concept refers nowadays often to the artificial selection, manipulation and breeding of organisms to bring about targeted, desirable changes in their genomic structure, Even though environmental adaption has also led to morphological and even genetic alterations (and this is one palpable reasons for the problems we have in taxonomic classifications) the greatest single factor has been human intervention and in this sense the most heuristic definition of domestication is ”that condition wherein the breeding, care and feeding of animals are, to some degree, subject to continuous control by man” (Hale, 1962). Man went, as the saying goes, from capture to culture.

CULTIVATION AS THE HIGHEST FORM OF CAPTURE

However, this supposedly linear progression has metamorphosed into more of a centripetal force since, with the increase in cultivation and further decline in capture, more and more attempts are being made to manipulate the genetic structure of the species cultured to improve existing brood-stocks, by providing a disease-resistant species, for example. And culture evolves to become an extreme form of capture.

So what has all this got to do with oysters, you might say? Well, possibly, it is the ultimate fate of the poor, sessile oyster, which minds its own business after its first two weeks of free-floating freedom as a veliger before looking for a homely piece of hard surface to settle down on and there remain for its entire life, that it becomes the perfect species to be domesticated, i.e. controlled by humans. It doesn’t provide any resistance nor register any form of complaint. Indeed, its very cultivation is a prime example of culture being the highest form of capture, because the oyster is removed from its very fixated position and becomes imprisoned in artificial environments, whether it be a hatchery, tank, bag, cages, crates or whatever, and where they are meticulously supervised by their human guardians. Aquaculture, often supported by landed businesses, can then exploit domestication to its logical ends, whilst fishing and fishermen are dismissed as a leisure-time pursuit and fade, like their wild stock, into a nostalgic past. It has been estimated that 97% of aquatic species present in aquaculture have been domesticated in the last 100 years, proving the rapidly developing dependence of aquaculture on domestication, which has been mainly due to the huge diversity of marine taxa and increase in our technical and scientific knowledge (Duarte, 2007).

DOMESTICATION AND ARCHAEOLOGY

As Jacques Cauvin, the French archaeologist pointed out (1994), domestication of animals was preceded by a symbolic process, whereby the spirit of the animal needed to enter into the human psyche, most likely with the help of shamanistic and burial rituals, so that some power over the wild would first be exercised on a mental and social level. Another way of expressing it would be to say that the animal world had to be humanised. We were forced into a relationship, and understanding of that wild world around us which was mediated by various ritualistic and symbolic enactments. Another archaeologist, Ian Hodder, took his cue from some earlier work of Cauvin and argued that ”the domestication of wild cattle and of the external wild more generally could thus be seen as an attempt to domesticate and control internal and social problems.” Further on he simply states that ”the process of domestication – the control of the wild – is a metaphor and mechanism for the control of society” (1990, 12), although I think it fundamentally concerned the process by which we learnt primarily to regulate ourselves. But that leads us into another bewildering world. Although man has long since moved away from the sea, from the original cave dwellings and huts on stilts on its endless shores (maybe partly due to a growing consumption of shellfish) and moved off into the interior, where the techniques of agriculture were mastered and safe settlements established, the sea had managed to retain its image and lure of a mythic space, boundless, unfettered and eternally free.

Although it seems as though oysters have been harvested for over 6000 years, according to the archaeological record, it is obvious that since the end of the 19th century, oysters have been more and more sucked into what now is called aquaculture after having been a source of subsistence food for the age-old community of hunter-gatherers, as typified by the fishing peasants along the Atlantic coasts of France and Ireland or by the Native Americans and later the watermen on the Chesapeake Bay, until overfishing, greed, urbanisation, pollution and, above all – overconsumption helped to deplete stocks. But even before all this took its toll, it was obvious there were other developments afoot to make oyster gathering more efficient, to regulate oyster reproduction, to privatise the foreshore or to build special oyster ponds (owned by the landed). The oyster couldn’t be left to itself to control its own destiny. Man had to step in to find ways to increase stocks for himself to fish.

CIVILISED OYSTERS FOR THE CIVILISED

Pascale Legué, a French anthropologist and urbaniste, wrote an inspiring book in 2004 about oyster cultivation in the Marennes-Oléron area, and pointed out the progression of the space of oyster management as it changed from the shore, to the marais and claires of the former salt-pans, to the cabane, the work-shed, a clear inland move from the sea, the foreshore to the land, where the work of sorting, grading, cleaning, bagging, packing and purifying has been performed. This can mean that the commercial oyster may be handled as many as 40 times during its life cycle, and becomes more a personal property and creature belonging to its patron than a fruit de mer. Indeed the whole process of cultivation in the claires engendered a new set of new values, its own tradition of savoir-faire, and this added to the oyster’s status as a specialty, especially important on festive occasions, when oysters were considered to be the best food to offer – «C’est ce que on a de meilleur » (2004, 206). The wild oysters, which increasingly were the Portuguese oyster, Crassostrea angulata, gathered on the seashore were for the hoi polloi, not good enough for the tables of the bon-vivants, the well-to-do. There was something unbecoming and distasteful about the wild, uncultured and seascaped oyster. It used to be common to refer to the invasive Portuguese oyster as “the oyster of the poor”, « l’huïtre du pauvre » (2004, 163).

The whole process of cultivation is also a metaphor for the way a wild species was brought into the human domus (home) rather than the other way round as it had been before. No, for the owners and their equals, only the oysters that had been nurtured through the entire process of élevage (cultivation) and affinage (refinement/finishing) could be deemed fit enough. Domestication served in this sense, as a sign of a civilised mind and set of values, and a release from the fear of our savage instincts. So this symmetry of refined oysters for the refined members of the human race and wild oysters for the wild ones seems almost perfect! That is, as long as we don’t accuse the French of being snobs about their food!

So, according to Legué and the traditions of the Marennes oyster-growers, the only oysters that could be consumed were those that had been farmed (élevée) and then refined (affinée), their rubber stamp of human approval. However, as she added, there is nothing outwardly that distinguishes one farmed oyster from another wild one. Even though this may not be absolutely true, as there are certain tell-tale marks on some oysters that can help us to see differences, her point is that what we long for is something that is not at all visible or touchable. The shell is in a sense just a pebble (un caillou); its living part, that what we want to eat or taste, is hidden from us, and can never be known to us until it’s about to die. We cannot observe or become attached to its growth, its development, as we can with most other animals; we have only a relationship to this inanimate pebble, however beautiful it can be, that cannot respond or be brought into the human sphere. It seems more like a vegetable, and that is one reason why the French often say bête comme une huître! (stupid as an oyster) since it is so simply passive, helpless and can never be tamed (apprivoisée).

ARE OYSTERS EVER WILD?

Furthermore, the oyster is not “wild” really at all, quite the opposite! The notion that the oyster is wild is anthropogenic and in a way unfortunate, since from the oyster’s own perspective it is anything but wild; on the contrary it is singularly unassuming, docile, solitarily locked in its own world, staying put in perfect repose, looking after itself without any help from anybody, thank you very much. It is a perfect piece of self-regulating machinery. But if it is untouched or undomesticated by humans, then by definition it must be wild. So if it is a stone or just some “thing”, beyond the human realm, what can we domesticate? Nothing! It’s all a sham! But let’s look after them, just in case! Let’s catch ‘em whilst they’re young enough to swim around looking for something hard to settle on, rods, sticks, ropes – and why not Chinese hats (sounds a ball!) – and then later shut them up in bags, bins, baskets, boxes or whatever, almost as if it was an animal that needed to be put in a cage. Or let’s put them on the backs of lorries and ship them from one country to another so that they can grow more quickly and avoid contaminated water. For instance, some French companies buy spat in Arcachon or from land-based hatcheries, which is then shipped to Ireland, before being brought back to special areas in France so that they can formally be called by the appellation of that area, like the oyster Ostra Regal. And now they have been “bag-trained”, why not go one step further and dress them up and give them a shell manicure, by tumbling them every so often, which will give them such a polished appearance, such a rounded, handsome shell that will look ever so perfect on the restaurant table! Or else, they are given special names that often hide their hybrid provenance, but which sound good.

We put the oyster through this regime for our own sake, although, in my opinion, it is this aspect of ”not-me”, the alien in the oyster, that is one of the most powerful factors in the polarised sentiments the oyster often engenders in either hating or loving it! Because with the oyster as opposed to most other domesticated animals, no mutuality can ever be achieved (even though I recently read a story about a hospital in Chicago keeping oysters as pets for the terminally-ill!).

DOMESTICATION AS A FORM OF CONTROLLING NATURE

So all that the process of cultivation boils down to is a collection of controlling routines, traditions, methods that we have chosen to satisfy our needs rather than the oyster’s. Legué writes (2004, 207),«la domestication des huîtres tient exclusivement à leur confinement dans un espace accessible à l’homme, construit et amenagé par lui» (the domestication of oysters depends entirely on their confinement to a space, accessible to man, and built and managed by him). In this sense, it is more an issue of territorialisation than domestication.

So we have in our narcissistic world succeeded in convincing ourselves that what we do, our techniques, our savoir-faire, that we love and respect, is far more important to the oyster than anything else, which may to a certain extent be true! But anyway it’s the sea, that decides its taste, as well as the syzygies, the tides, the currents, the algae, in short nature, not us.

On the other hand, Legué seems to imply (2004, 252-4) that the progression onto the land freed the oyster-farmer from the vicissitudes of the elements that he had no control over, and he was able to develop skills and know-how that he could control. This in turn allowed him to change his mentality and attitudes that before (and in some cases still even today) imprisoned him in a narrow-minded, if not bigoted mind-set, which also caused damage and suffering. On the other hand, some of the rhetoric of cultivation, stewardship and know-how can mask a patronising attitude that accompanies the ideal of mastery and control over nature. The history of the Chesapeake Bay is a classic example of these conflicts (Keiner, 2010). However, it must be said that many traditional occupations of the sea have seen themselves overtaken and abused in some cases, by more land-based businesses that often run aquaculture companies. At the core of territorialisation, in this context, is the landscaping or expropriation of the sea by values and ideas that belong to the landed, urbanised and now indigenous population.

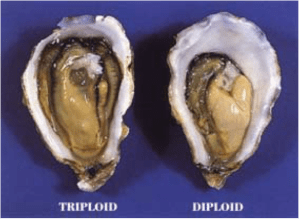

From this more anthropological perspective, there is a parallel between the territorialisation of the oyster-farming profession and also of the oyster itself, because it becomes transformed into a commodity, to be prepared for markets all round the country and overseas, at any time of the year, so that it can be consumed when we want. Yet, we call this activity sustainable, but for whom? Of course, it’s very sustainable for farmers, for consumers but is it for the oysters, which have been deprived of their “wild” identity, as sessile molluscs or for the environment, i.e. nature? There is some evidence that the oysters, especially the triploids, reared in hatcheries, become easily stressed (over-handled and moved around too often), and therefore are less able to cope with viruses and bacteria that are ever-present in the water-column. But this is all done to produce a more presentable oyster for seafood restaurants and the ever-expectant consumer.

Before, buying or eating oysters was more simple; in France, for example, you did it by numbers, as they were sold by sizes. Or you asked for oysters from a certain place, like Belon, or Cancale in Brittany. And in England, you asked for six Colchesters, or six Loch Ryans. Most of the finer restaurants in London still stick to that tradition. However, it’s becoming all the rage to give oysters fancy names. Names do stick and as with any food, labels, brands, provenance in some quarters mean everything, just like the trends in the later 19th century in America where Blue Points were the oysters everyone wanted and were served, whether they originated from there (on Long Island) or somewhere else, and in Paris where Belons were considered haut de gamme, the bee’s knees. The reverse side to all this, unfortunately, is the illegal traffic in oysters, articles about which appear in newspapers every so often.

DOMESTICATION AS HUMANISATION OF THE WILD

But now as we sit perusing the menu at any well-stocked oyster bar, into whose warmth and care, we and the raw, living oysters have been brought, we are mesmerised by the pretty names given to the molluscs we are about to devour and enjoy; and we want to find the perfect pairing of drink to wash them down with – all very civilised and all to calm those qualms about gnashing our teeth into the live flesh of those tasty molluscan morsels. Finally, the oyster has been “domesticated”; it has survived its circuitous journey to its final destination, our table. All these ritualistic ingredients are part of that domesticating process of not only the innocent, unknowing oyster but also of ourselves as waited-on restaurant guests. The humanising part of this process also aims at making the oyster consumable, edible, presentable, possibly more importantly so because the oyster is rarely cooked. Customarily, one of the characteristics of domesticated animals is that they are never eaten raw. On the contrary, it is the wild, the prey hunted, that may be eaten raw; among certain tribes, often it is considered an honour to drink the raw blood of the slaughtered animal before it is cooked, i.e the hunter becomes the hunted.

Our civilised rituals are, then, our sublimated way of entering into the spirit of our totem animal, that we humanise it, dress it up and overcome the “not-me” alienation that has dogged our relation with nature. We humanise nature, its species, at the same time as we see ourselves above or beyond nature, and maybe it was domestication that was our first act of hubris, when we decided to put ourselves above nature and bring nature into our domus (home), instead of realising that we were an integral part of this nature. In fact, domestication can be seen as verification of our innate fear of the wild, the raw and the untamed.

ROLE OF AQUACULTURE IN THE TERRITORIALISATION OF THE SEAS

Then there is the bigger question of aquaculture, which is one of the largest expanding areas in food production, since it is seen as a method of producing endless quantities of protein-rich food for the growing world population. Much could be sustainable but not all aquaculture is, despite certain popular perceptions, and we really need to think about the long-term effects of damage to the marine environment that certain aquacultural practices cause around the world. There is no doubt that, given its increasing mechanisation and automation, aquaculture is beginning to resemble its agricultural cousin. The sea has mainly been regarded as “the common heritage of mankind”, according to the UN Law of the Sea, but in the view of many suffered just because of this. According to the theory of the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968), this is why overexploitation occurred, and in the end the only viable solution was some form of restriction, which in the guise of current political ideology was interpreted to mean privatisation or leasing of the seas and shoreline. The oceans are being used more, not just in the sense of deep-sea fishing or offshore or open ocean aquaculture, where raft-culture, for instance, with shellfish can take advantage of the stronger ocean currents. In some places, disused oil rigs are being converted into aquacultural facilities. The ocean is being “industrialised” in more ways than one: deep-sea exploration and sea-bed mining, offshore wind-farms, tidal power and wave energy generation, even the use of the ocean as a gigantic dump-site – all point to the growing territorialisation of our seas, and aquaculture plays one part in this “industrial” process. The oceans have long been the last frontier on the planet for man to penetrate. This fantasy extends even into the brainchild of some libertarians who envisage the foundation of ocean settlements, called “seasteading communities”, freed from any state interference.

Garrett Hardin foresaw a scenario where if the tragedy of the commons was not solved, annihilation of the human race was inevitable. There was no technical solution, because what was required was a radical change in the way we lived and the need for mutual coercion in imposing certain necessary restrictions on our freedoms. On fishing the oceans, he wrote this a few years later (1974), but amazingly enough 40 years ago, given that this is still as depressingly true today as it was then:

[talking about the destruction of common resources…] The same holds true for the fish of the oceans Fishing fleets have nearly disappeared in many parts of the world, technological improvements in the art of fishing are hastening the day of complete ruin. Only the replacement of the system of the commons with a responsible system of control will save the land, air, water and oceanic fisheries.

His words have been used as an excuse or justifications for the implementation of private ownership as the only way forward to secure sustainable stewardship of such common resources, and he was probably all in favour of such a solution himself. But as many have pointed out, such as the famous economist Elinor Ostrom, there are in fact many other solutions to managing common resources that can successfully involve local communities preserving and containing marine areas and species. But the march towards privatising the commons, the seas beyond national territorial boundaries goes on with relentless force.

So just as domestication rested on a need to tame the wild, territorialisation also seeks control the unknown, the unfettered, in this case the commons of the seas. In a way, this territorialisation can be viewed as the final instalment of our slow, self-imploding drive to see it as a right to exploit nature, as we return once again to – and we may just long for – our watery origins. Maybe the circle will close and the seas our final destiny, our primordial beginnings, into which we risk disappearing, unless we successfully solve the dire problems of global warming on our oceans (Charter, 2007).

REFERENCES:

Cauvin, J. (1994): Naissance des divinités. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Charter, R (2007): Life on the Edge: the Industrialization of our Oceans.

Duarte, C. et al (2007): Rapid Domestication of Marine Species, Science, 316, no 5823, 382-3.

Hale, E. B. (1962): Domestication and the Evolution of Behaviour. In E. S. Hafez (ed), The Behaviour of Domestic Animals. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Hardin, G. (1968): The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162, no 3859, 1243-8.

Hardin, G. (1974): Lifeboat Ethics: the Case against Helping the Poor. Psychology Today, 8, 38-43.

Hodder, I. (1990): The Domestication of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kleiner, C. (2010): The Oyster Question. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

Legué, P. (2004):La moisson des marins-paysans. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.